When George Eastman launched the Kodak No. 1 in 1888, his key move was not only technical innovation but a complete redefinition of photography where anyone (including children!) could take pictures. Early Kodaks came pre-loaded with film and were sold with the promise that the company would take care of the messy, expert work of development and printing. The slogan “You press the button, we do the rest” encapsulated this new division: consumers performed a simple gesture, while the company handled everything else, turning photography into a streamlined consumer service and memory industry.

By 1900, the one?dollar Brownie box camera pushed this democratization further, especially among children and lower?middle?class users in North America and Europe. Abundant, cheap snapshots transformed family visual culture: where earlier households might own a handful of studio portraits, now they could accumulate rolls of informal pictures of everyday life, holidays, and travel. Kodak’s advertising and instruction manuals taught people that “good” photography meant recording happy, intimate moments, like birthdays, outings, and children at play, while minimizing pain, conflict, or death. In doing so, the company effectively shaped what counted as a “memory” worth keeping.

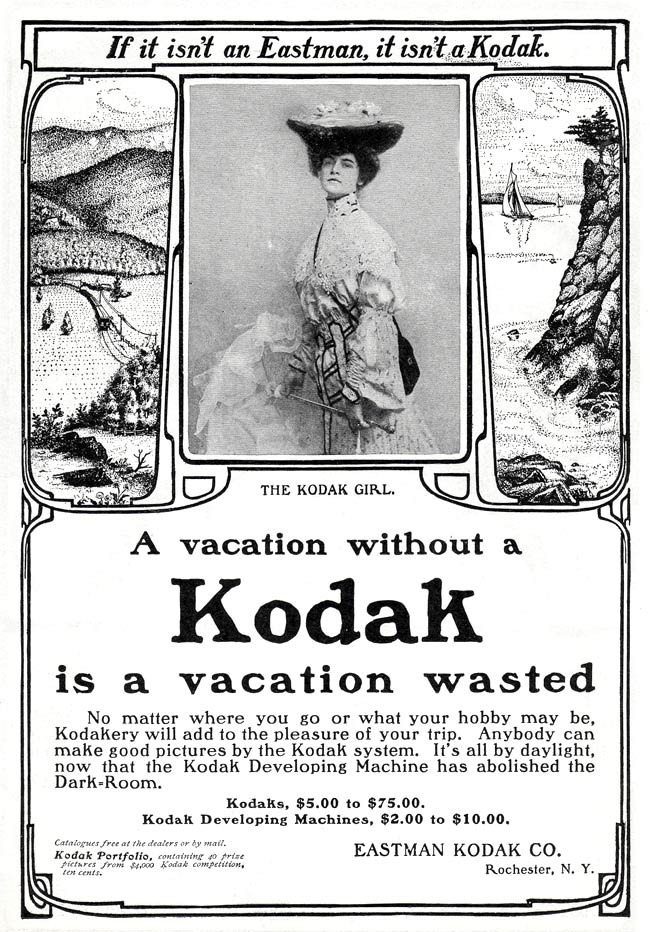

Within this expanding market, Eastman Kodak needed a human figure to embody the promise of easy, pleasurable picture?taking: the Kodak Girl. She appeared in the 1890s in American and European advertising as a young, stylish woman whose portable camera signaled both technological modernity and social freedom. In early campaigns, she often moved through outdoor or travel settings like parks, beaches, world’s fairs, alone or with other women, rarely accompanied by men, which aligned her with the “New Woman” who was mobile, independent, and leisure?oriented.

The figure of the Kodak Girl represented several things. She made cameras seem unintimidating by suggesting that photography required no special strength, technical mastery, or masculine expertise. Her youth and breezy femininity softened the face of a powerful corporation, turning a global manufacturing and distribution machine into something intimate and friendly. And because she was shown constantly in motion. She linked picture?taking to modern mobility and consumption: travel, fashion, and the purchase of new accessories for each occasion.

By the 1920s and 1930s, the Kodak Girl also became explicitly fashionable. Vanity Kodaks and other models were marketed as color?coordinated accessories, designed to match women’s outfits and presented as “smart gifts” for the graduate or bride. In these campaigns, the camera was as much about being seen—carried like a clutch purse or dangling stylishly from a wrist—as about seeing and recording. Carrying a Kodak was framed as part of a modern woman’s public persona.

As Kodak consolidated its dominance, it repositioned women not only as glamorous users but also as domestic memory workers. Instructional texts and magazines such as Kodakery repeatedly cast mothers as the principal family photographers: the ones who were always present at baths, first steps, school days, and backyard play. Advertisements and manuals urged women to capture “everyday” scenes, such as children in soiled clothes, messy kitchens, and laundry days, insisting that albums would be incomplete if these “small things” were left unrecorded.

This discourse folded photography into women’s unpaid domestic labor. Mothers were encouraged to feel responsible for producing a continuous, coherent visual record of family life, and guilt was mobilized when gaps appeared in the “story.” Over time, snapshot practices created a highly selective archive of happiness: celebrations, holidays, healthy children, new consumer goods, and homes, while conflict, illness, and grief seldom appeared. Scholars have argued that Kodak thus commodified nostalgia itself, teaching people to understand their lives as sequences of consumable “Kodak moments.”

At the same time, advertising often used a younger female figure—the daughter—as the visible camera holder: the Kodak Girl inside the family, eager to photograph her parents, siblings, and friends. In these images, the girl’s modernity and youth are affirmed, but the horizon imagined for her is still domestic: she will eventually become the mother?historian of her own family.

Kodak’s interwar campaigns, particularly in Britain, linked this feminized image of photography to larger ideas about nation and empire. Advertisements in British magazines and newspapers presented a middle?class family, often centered on a daughter with a Kodak, touring the countryside or seaside and freezing “beautiful England” in a series of reliable snapshots. Here, the Kodak Girl became a key figure in a broader reimagining of “Englishness” as domestic, decent, and reassuringly feminine after the trauma of the First World War.

The camera offered to “stop time,” preserving an eternally youthful family, an unchanging countryside, and a stable social order at a moment when class relations, gender roles, and imperial power were in flux. Fathers sometimes appeared in these ads, but often as slightly comical figures—getting “younger” when they use a Kodak—while the daughter or young woman was shown as emotionally attuned and alert to fleeting moments. The Kodak Girl thus mediated between modern technology and conservative values: she ushered consumers into a new mass?produced visual culture while promising that cherished identities—home, nation, family—could be safely preserved.

As Kodak’s global reach expanded, this feminized visual language traveled with the brand into imperial and postcolonial markets, including India. The Kodak Girl became a portable template that could be adjusted to local conditions, especially race, dress, and family structure, without relinquishing her core functions of selling cameras, memories, and a particular version of respectable modern life.

In India, Kodak operated through a British?controlled subsidiary and initially used the familiar white, striped?dress Kodak Girl in newspaper advertising, depicting her as a modern tourist moving through “exotic” colonial landscapes and photographing compliant local subjects. These images reproduced colonial ways of seeing: the white woman’s gaze ordered and collected the colony, while the camera stood in for imperial authority.?

By the mid?twentieth century, however, Kodak and its competitors had to address a growing Indian middle class and a changing political environment. In this context, the Kodak Girl was localized. Advertisements in Indian magazines show a sketched female figure with a camera wearing a sari, bindi, and sometimes a covered head; she appears at the margins of camera and film adverts as a small but persistent emblem of the brand. This “Indian Kodak woman” fused the global corporate icon with signs of respectable Indian femininity.

At the same time, photographic adverts in illustrated weeklies and film magazines staged model families in carefully composed scenes: a Western?dressed father photographing his child, while a sari?clad mother stands slightly behind, watching proudly; or a wife playing the sitar in a modern interior while her husband crouches with a Brownie camera to record the scene. These layouts often doubled the image: one frame showed the “real” domestic tableau, and another inset or implied frame suggested the snapshot that would be taken.

Gender roles and colonial/postcolonial hierarchies intersected here

Copy and visual cues suggest that these families are urban, middle?class, and aspirational, inhabiting new suburban neighborhoods, owning cars, and participating in national modernization. Cameras and film are presented as integral to this lifestyle: tools for recording education, festivals, holidays, and the construction of new homes.

Other companies—Agfa, Gevaert, and Indian brands—also increasingly used young women with cameras in their advertising, sometimes placing them outdoors at monuments, beaches, or in rural landscapes. In one Agfa campaign, for instance, a sari?clad woman is shown photographing a man, with taglines that tie romance, travel, and photographic pleasure together. These images echo global Kodak Girl tropes of mobility and flirtation, but they are inflected by local ideas about modesty, conjugality, and “respectable” female visibility.

In this colonial and early postcolonial context, then, the Kodak Girl did more than sell cameras. She helped naturalize a consumerist, image?based modernity within domestic and national life, while smoothing over sharp political and economic asymmetries. Cameras were imported goods tied to foreign capital and Cold War trade regimes, yet they appeared in advertising as intimate companions of Indian families, festivals, and patriotic feeling—especially when campaigns urged people to photograph soldiers, national leaders, or “life in India.”

Across these different settings, the Kodak Girl and her localized doubles condensed several overlapping meanings. Her effortless handling of the camera dramatized Kodak’s promise that photography was simple, safe, and available to non?experts. She represented a particular form of femininity that modern America wanted to imprint upon- a new female subject who was active, mobile, and visually literate, yet still aligned with normative ideals of domesticity, respectability, and consumption. She embodied memory and nostalgia: By appearing in scenes of play, travel, courtship, and family life, she stood for a particular way of living in time—collecting “good” moments, warding off loss, and turning the past into pleasurable images that could be revisited indefinitely. In colonial and postcolonial worlds, her image mediated between global corporations and local publics, translating a transnational brand into familiar cultural codes and helping to domesticate wider structures of technological and economic domination.

By the time Kodak retired the Kodak Girl campaign in the 1970s, women were firmly established as both everyday and professional photographers, and snapshot photography had become a routine language of self?presentation and social memory. Yet the legacy of the Kodak Girl—and of her Indian descendants—remains embedded in how cameras, gender, and family histories continue to be imagined: as light, effortless, and above all, as “natural” extensions of women’s work and women’s lives.