The Technical History:

The Magic Lantern (in Latin “Laterna Magica”) was first visualized by Leonardo Da Vinci, who is said to have experimented with projected images. The Dutch physicist, Christian Huygens (1627-1695), is generally regarded as the inventor. His apparatus projected pictures painted on glass plates with an oil lamp as the light source. While its structure did not change significantly, photography soon replaced paintings. Initially, the lamps and candles used provided a dim (and almost ghostly) projection on the images. They were eventually replaced with electric bulbs. These images, when projected in a darkened room, created a sense of immersion, transporting audiences to far-off places, including landscapes, monuments, and people.

Theatrics and Illusion:

It might be hard to imagine the reaction of a crowd that did not understand projection when this technology was first introduced. It might have ranged from being overwhelmed to being scared, given that magic lanterns were widely used in open theatrical plays and, unsurprisingly, in magic shows! From the moment of its invention, the magic lantern became part of a Baroque culture fascinated by the world of illusions. Street performances were ubiquitous, and the general public of England (who were largely illiterate) relied on these acts to understand current social and political events. Magic, of course, held a significant space amongst these performances. Plays about mythologies relied on magic lanterns and their ‘ghostly’ projections to give a sense of the supernatural. The shadowy images on the wall often resembled dreams, prophecies, visions, or even demonic apparitions summoned by the magicians. Even people could be brought ‘back from the dead’!

With early magic lanterns, which ran on candles and lamps, it was easier to produce hazy projections in a darkened room, giving the illusion of ghosts. This invention gained popularity in the public sphere, as travelling projectors were demonstrated in fairs, halls, and even royal courts.

Their Function in Colonization:

While theatres and public plays were crucial in disseminating current events to the general audience, magic lanterns were foundational to how a large chunk of the British population (especially children) learnt about their country’s mission to “civilize” other regions. With the decrease in the slide size, photographic slides also became popular. A reading accompanied these slides.

It is known that photography came to colonial India just six months after its invention. It quickly became the preferred medium of the British Government for recording, documenting, and characterizing the “unknown” and “dark” land of India, its monuments, and its many different social groups. Government officers and military doctors who traveled frequently became amateur photographers and were tasked to essentially ‘put a face’ to what India or an Indian was. These photographs were displayed in Photographic Societies, but they were also used in magic lantern shows and accompanied by extensive lectures by the photographer for both officers who had never been to India, and children who were unaware of their country’s movements. Let’s look at three broad categories of how magic lanterns were used to spread knowledge about India’s colonization.

Throughout Britain’s colonization of India, only a tiny portion of the British population had actually seen India. It’s quite shocking to think about how a majority of Britons relied solely on paintings and photographs of Indian landscapes and people as they were printed in journals and newspapers, and reenacted in street plays. One can then wonder how children, the next generation of officials who would play an active part in the ‘civilizing mission’ in their colonies, would learn about the British Empire. This is where magic lanterns come into the picture.

In 1907, the Colonial Office Visual Instruction Committee (COVIC) employed the artist Alfred Hugh Fisher (1867-1945) to document the land and people of the British Empire through photography. These photographs were made into lantern slide sets and reproduced in textbooks for children’s geography classes. This was part of a larger endeavor—one that sought to correct the historical mistake that the British population lacked knowledge of the British Empire’s history and geography. These slides, accompanied by a reading and a lecture by the photographer, were used to indoctrinate children.

These illustrated lectures were also used in the colonies, including India. While British children learnt about the colonies, children in the colonies learnt about Britain (the ‘Mother Country’). For British children, these lectures were crucial in instilling patriotism and fostering awareness of the ‘greatness and vastness’ of the British Empire. Children were shown the work the British Government was doing in India, such as expanding the transport infrastructure, as well as ‘typical’ scenes of villages and ruins of great monuments to emphasize their civilizing mission. These photographs were intended to evoke sympathy among British children and make them take pride in the British Empire.

Photography became the gateway through which Britain also documented and classified India’s diverse population. A notable example of this is the 8-volume photography album titled The People of India. The photographs were accompanied by a title and text, which described the people and their mannerisms. These volumes were foundational to the British Government, which sought to put a face on the people it ruled. This was especially needed after the Revolt of 1857, which made the colonizers extremely anxious about their position. The People of India used photographs to create strict stereotypes about the many social groups spread across the continent, with many being classified as thieves, liars, and violent.

These stereotypes were reinforced as more photographs were taken, and this knowledge was disseminated across Britain through media such as newspapers and magic lanterns. COVIC’s representation of different groups reinforced the idea that they were the ‘other’, and placed them at a lower racial value than the British. This fostered the binary separation between the colonized and the colonizer, further reinforcing the Government’s mission to ‘civilize’ these groups.

Indian religious people and festivals were a great source of fascination to the British. The fascination stemmed from the fact that it was a new spectacle that they could document and write about. Fear, however, dominated this interest in Indian religions because their beliefs were considered to be contrary to those of Christianity. Islam and Hinduism were seen as religions that continued to make India ‘backwards’, and the British were especially fearful of figures like fakirs and religious processions like Muharram because they found them unruly.

According to colonial ideology, fakirs, as religious saints and ascetics, were seen as representatives of Hinduism and Islam. Religions such as Hinduism baffled the British due to their many gods and forms of veneration. These ascetics were considered to be ‘filthy’ and a representation of a religion that was steeped in error and superstition. Magic lantern slides often depicted fakirs as naked or barely clothed. They were also shown performing extreme tasks, such as sitting and praying on a bed of spikes, as a way to worship their Gods. These were perceived by the British as fanatical in their lantern readings and lectures. Most of the texts anchor the readings squarely in ‘official’ British accounts of fakirs: their dirt and their eccentric, irrational behaviour, which was representative of the dangers out there.

In Muharram, which commemorates the death of Muslim martyr Husayn Ibn Ali (son of the fourth Caliph, Ali), large processions are held in towns. The British Government, which considered Muslims to have a propensity towards violence, feared the gathering’s large crowds and mourners to be disorderly and prone to riots and conflict. Lectures that accompanied the magic lantern slides about Muharram also mitigated this fear. Since Muharram was considered to be ‘the’ religious observance that represented Islam in India, the British were obsessed with documenting and writing about it. It is through these lantern slides that stereotypes that these gatherings incite communal violence among Hindu and Muslim communities were circulated. The British fear of rioting led them to overlook the fact that most Muharram processions were peaceful. The textual emphasis in lantern readings on the hazards of Muharram, therefore, constrained other readings of the image, such as its bustling, crowded character.

Conclusion:

Magic lanterns were far more than quaint Victorian amusements; they were engines of learning, spectacle, and imperial storytelling. Their luminous images brought colonial India to British audiences in vivid color and narrative detail, fostering not only curiosity but also structured modes of seeing shaped by power and distance.

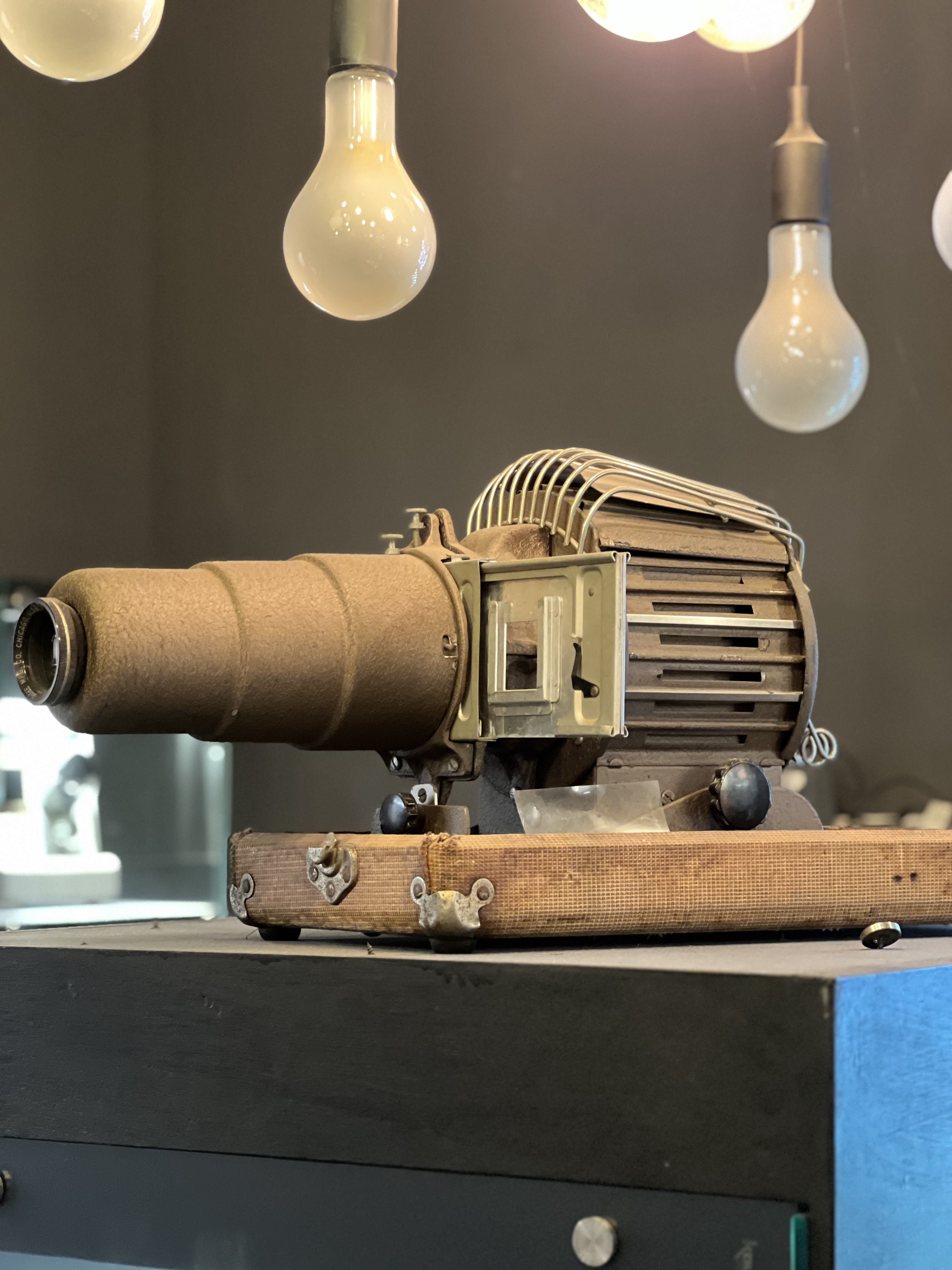

Museo Camera also houses a spectacular collection of Magic Lanterns from the 19th and 20th centuries in its museum display, with a demonstration of how they projected photographs. By revisiting how these devices illuminated India for British eyes, curators contribute to a broader conversation on the making—and remaking—of visual histories.

Want to know more about magic lanterns? Visit Museo Camera today!